Do you remember the roll-down posters we had in elementary school science labs? The ones that illustrated different ecosystems, usually by layers? I was probably the only kid that would sit and stare at them during class. I can’t explain it, but those posters fascinated me. I was so vocal about the art that my second grade teacher gave me a poster with prehistoric era illustrations; I have it framed in my office right now.

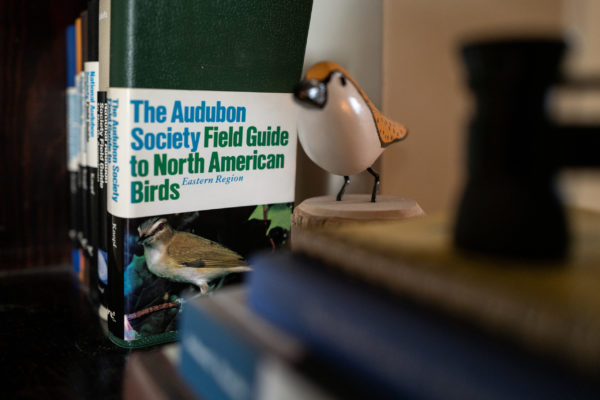

It could be an appreciation of wildlife. Growing up in Eastern Kentucky, I would often catch a glimpse of different animals, but never long enough to admire them. I had no idea who J.J. Audubon was when I found the Audubon Society’s Field Guide of North American Birds sitting on a shelf in an old consignment store. The book was obviously well-loved but totally worth the asking price of twelve dollars. I should note that I don’t typically buy just any book or thrift find; this book seemed to open up a door to a new interest outside the realm of filmmaking. I didn’t know where it would take me, and I didn’t think birdwatching would ever be on the agenda. I’ve had this guide for some time, admittedly never using it. I know, it’s a crime.

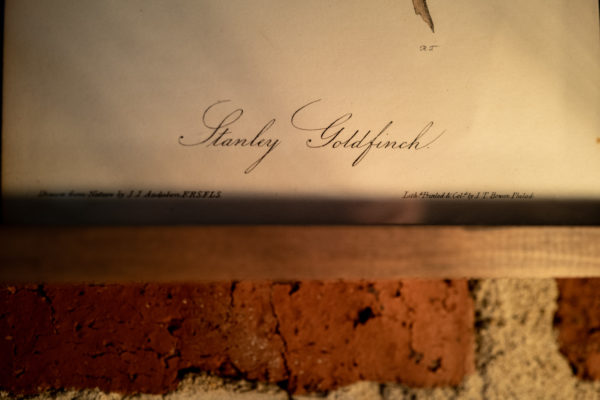

Another book has sat on my shelf unnoticed, gathering dust until relatively recently. It was an online auction, and up for bidding was a Stanley Goldfinch print from an early 1900s Birds of America book. I would like to claim that it was an intense bidding war, something worthy of bragging. I won it for twenty dollars. While it may not have any incredible value for collectors, it’s the oldest thing I’ve ever held. It’s also the most beautiful thing I can say that’s mine.

I was location scouting for an interview we had to film on Berea College’s campus. I was pointed toward the library for being the quietest place for filming. I owe an apology to the person showing me around because when we walked in, front and center of the library was a John James Audubon’s Birds of America edition on display. It was in a glass case, opened to show only one page. I abandoned my tour guide. I sat the equipment down and stared at this magnificent book like I did those old biology posters. There it was again, this fascination with an art form that I didn’t even know the appropriate name for.

It had been a few years since then, my moment of being in front of the holy grail of wildlife art, when an opportunity came knocking for a film series about Berea, focused on different tourism elements and the people who work behind the scenes. I was brought on as the director for the series, so I had a little room to pitch stories that could work as short films. Coincidently, I had just recently moved to Berea to work on another project and was still settling into my new apartment. This is important because my walls were still relatively bare, and the only thing I had hung up was my Goldfinch print above where I read. When brainstorming ideas for the series, I showed up and pushed to do a piece about the Birds of America collection in Hutchins Library. I saw my print every day, so before every meeting about the series, I came with that print in mind.

I had no idea how I would film an episode about a ridiculously oversized book with pictures of birds in it. I believe part of me just wanted to see it again to admire it. Going into the shoot with a few pages of storyboards and only a rough idea worked to my advantage because the story unfolded naturally. I treated the books as I do in real life; as works of art. Tim would flip the pages, and I would get another eye-full of beautiful artwork. Each page looked as though the ink had just settled, and the artist had just left the room. Despite how well we could light or film the book, there was no chance of representing the craftmanship that went into the collection. I hate to sound so cliché by saying you have to see it to experience it, but you do. I filmed this episode as an admirer, and I’m ready to go back and see it again. It’s something that I know I will revisit throughout my life.

In our interview, Tim made a point that birdwatchers would really appreciate the Audubon book. But for me, it worked in reverse. I wanted to make that connection in the film, so I went birdwatching for the first time in my life. As a documentarian, I have filmed many subjects and scenarios, but I learned rather quickly that I was not equipped to film birds. I was fortunate to have excellent guides who helped me, but I saw more birds than what made the cut in this video. Bird photographers: my hats off to you! Your hobby is wild and frustrating, and I love it. I must have known something special was on its way when I bought that old field guide. Was it this film? Maybe. I hope this film propels someone else to admire the artwork, take up birdwatching, or more. I’m sure there’s a kid out there who sits and stares at the roll-down biology posters in his classroom. This book would probably blow his mind. I take walks in the woods now, looking for birds, usually finding a few that I return home to look up in my field guide.

Speaking of the field guide, you will see a clip of Tim holding a book when he and his wife are out birding. No, it’s not mine. When we were out filming, he brought some of his usual birding equipment, and in his hand was his field guide. I remember excitedly saying something entirely out of context about having that same book at home! I was the only one there that day, quietly having a revelation – in the middle of Brushy Fork. It was hard to ignore that an old dusty book in a consignment store had led me here. Those were the best twelve dollars I ever spent.

– Justin Skeens